Industry Insights (March 2023)

The inside track on property development in March 2023.

Industry Insights

Industry Insights

Planning permission: the dreaded process that's deterring more and more property developers. With recent reports showing drastic drops in applications in England, this month’s Industry Insights looks at the stats and the consequent effect on the future housing market.

Planning applications and permissions are ‘falling off a cliff’

One of the biggest problems developers are facing is achieving planning permission. A recent conversation we had with a London based commercial property agent told us that planning applications and permissions are ‘falling off a cliff’ in their area. As such, they’re predicting severe shortage of new stock by 2025.

Not great news for future house-hunters and businesses looking for premises, but ideal timing for developers buying today’s shovel-ready developments.

To tackle the problems levelling up secretary Michael Gove announced various new measures this week - but critics are suggesting it is too little, too late.

We decided to delve a little deeper into the topic, to understand the issues at play.

Looking at the planning stats

So how bad is it?

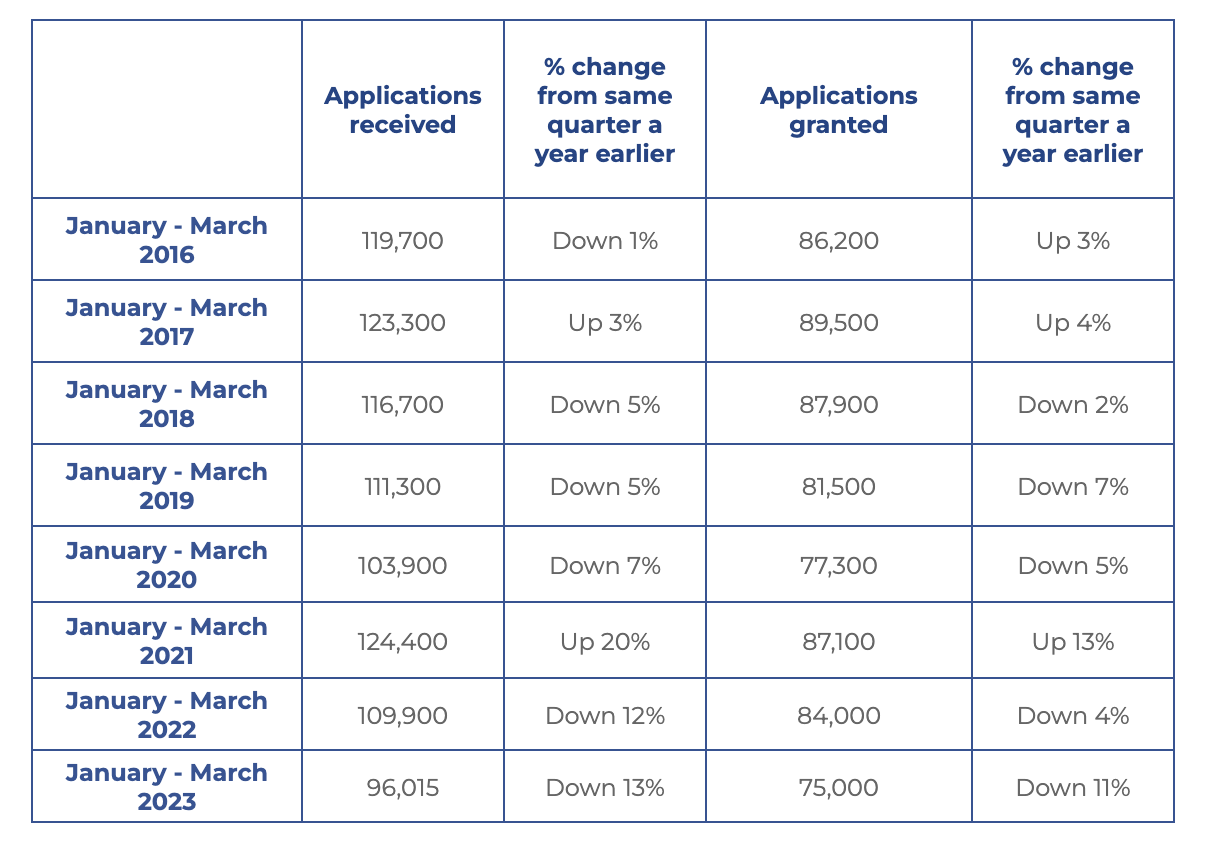

The most recent government figures for England, published last month, show a plummet in applications: between January to March 2023, planning authorities in England received just 96,000 applications for planning permission. This is 13% lower than the same quarter last year. Of those, 75,000 decisions were granted, down 11% from Q1 2022.

Looking at the same stats over a seven-year period offers some perspective:

Comparison of Q1 planning applications and applications granted in England:

Other than anomalies caused by the pandemic, the figures show planning application submissions have been steadily declining since 2017.

If we break the data down further into each quarter over the past 24 months, we can see the same gradual decline overall.

Planning application statistics, England:

Department for Levelling up, Housing and Communities

These figures outline the numbers of whole planning applications submitted and granted and include all types of development; residential, infrastructure, commercial & retail, hotel, leisure & sport, industrial, medical and healthcare and education.

A Report by The Housing Pipeline states that 3,037 housing projects were granted permission in Q1 2023 - the lowest quarterly figure on record.

It reflects a 20% decline in housing projects granted from the same quarter a year earlier and an 11% decline from Q4 in 2022. The report also states that the number of housing projects approved over the course of 2022 was already at the lowest level since the dataset was started in 2006. Affordable Housing-led developments and small sites saw the greatest drop, with a 41% drop in permissions for Affordable-led schemes compared to the same quarter last year and the lowest number recorded for small sites granted permission since the dataset began in 2006. (hbf.co.uk)

If we drill down into the actual number of housing units granted for development, Q1 2023 has seen the largest quarter-on-quarter decrease in 13 years.

Number of housing units granted planning permission in England, up to the year ending March 2023:

Source: Glenigan

The number of residential units granted permission over the last 5 years is, in some instances, double than what was granted each year in 2009 and 2010, but the figures have to be considered alongside our population.

The compound effect of less housing and more people

In 2009 the UK population was 62.28 million, with 52.2 million in England. Today it’s 67.7 million, signifying a growth rate of 0.34% per year.

In 2022, net migration saw 606,000 more people arriving long-term than leaving - an increase of 118,000 from 2021 and nearly double that of pre-pandemic and pre-Brexit levels. (ONS).

As we know, the UK already has a housing shortage, estimated to be between 1.5 million and, at the higher end of the scale, 4.3 million (Centre for Cities). A housing deficit of 4.3 million would take at least 50 years to fill, even if the now-extinct target of 300,000 new homes per year had been achieved. Tackling the problem sooner would require 442,000 homes per year over the next 25 years or 654,000 per year over the next decade in England alone (centreforcities.org).

For context, ONS house building statistics show that in the financial year ending March 2022 there were 204,530 dwellings completed in the UK.

If population growth and net migration continue on the same trajectory, the housing shortage will grow exponentially.

So, what’s the problem with planning?

It’s a big question: under-funding, under-staffed, flip-flopping government policy, lack of confidence/trust in the department, discretion being at the core of decision making.

Reform is long overdue to address a planning system that has remained fundamentally untouched since its introduction in 1947.

Policy: The current government’s housing policy has see-sawed drastically, with the 2019 target of building 300,000 new homes per year later ditched by Liz Truss in Sept 2022, briefly reinstated by Michael Gove, only to be ditched again in December 2022. Scrapping mandatory house building targets caused 58 local authorities to suspend their own development plans.

According to Stewart Baseley, exec chairman of the Home Builders Federation, 'The collapse in planning permissions is a direct result of the Government's increasingly anti-development policies and negative rhetoric. The social and economic consequences could be felt for decades.' (thetimes.co.uk)

Under-funded, under-staffed: A decade of budget cuts has left local planning authorities chronically under-staffed. Problems go back to 2008, when the recession forced redundancies – since then wage growth has been limited and caseloads have swelled, pushing people out of the role. Meanwhile, policy is growing in complexity and specialisms like heritage and sustainability are under-resourced. A gap in expertise is compounding problems, with reduced funding and a loss of senior staff leading to a gap in training and expertise. (p4planning.co.uk)

All of which impedes on the service staff can offer and the timeliness of decisions. According to the Local Government Association (LGA), a ‘crisis in recruitment’ within local planning authorities has created a bottleneck that is slowing down the progress of projects.

In a recent survey of SME builders by The Homebuilders Federation, staff shortages were considered the biggest constraint to developers:

Source: The Homebuilders Federation

Put simply, planners are overwhelmed.

The overly complex processes: Planning in the UK is devolved across all four nations, meaning there is no central rulebook. ‘Instead, there are multiple acts spanning decades [with] endless sticking plasters, endless changes, endless levels of environmental reviews and design reviews that the council must take into account.’ (Freddie Poser, director of Priced Out, Raconteur.net)

Planners have to consider a plethora of elements: ground conditions, land stability, ecology, drainage, flood risk, highway safety, travel plans, sustainability, trees, biodiversity net gain, impact to the landscape, noise, air quality, energy, heritage, listed buildings and public engagement. Combined with location considerations: National Parks, Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty, the green belt, and conservation areas.

Thus a simple project, such as the demolition of a two-storey building in Enfield and replacement with four tower blocks required 195 documents. This included a response from Sport England on increased leisure demand (swimming pool demand would be raised by 0.04 pools, plus 0.05 rinks of an indoor bowls centre).(Raconteur.net)

Nutrient Neutrality: To reduce nutrient-pollution in rivers, Natural England imposed restrictions on 74 councils across England, affecting around 145,000 new home starts. Despite the main causes of nutrient-related river pollution being run-off from agricultural activities and the failure of water companies to maintain infrastructure, the government continues to support nutrient-neutrality regulations on home building whilst recently reversing a plan to reduce the use of high-nutrient fertilisers by farmers. It is estimated that all existing development, including residential, commercial and the rest of the built environment, contributes less than 5% towards the phosphate and nitrate deposits in rivers. (hbf.co.uk)

Nutrient Neutrality: To reduce nutrient-pollution in rivers, Natural England imposed restrictions on 74 councils across England, affecting around 145,000 new home starts. Despite the main causes of nutrient-related river pollution being run-off from agricultural activities and the failure of water companies to maintain infrastructure, the government continues to support nutrient-neutrality regulations on home building whilst recently reversing a plan to reduce the use of high-nutrient fertilisers by farmers. It is estimated that all existing development, including residential, commercial and the rest of the built environment, contributes less than 5% towards the phosphate and nitrate deposits in rivers. (hbf.co.uk)

Down to discretion: The discretionary element in the UK planning system is potentially the biggest problem however, with extreme differences in project approval across different local authorities. For example, Wigan, Isles of Scilly, and Richmond approve more than 95% of applications; in Maldon and East Hertfordshire over 40% are denied. (leaderfloors.co.uk)

Often two planning officers have opposing views on the same project so applications can be rejected only to be rehashed in near identical form and given the green light by another planning officer. (In Scotland, less projects will achieve permission on second application after recent planning reforms prevent approval for projects similar to anything that’s already been denied within the past 5 years).

Politics also plays a part – decisions on applications with 10 or more residential units are made by local councillors who can override the planning officer’s recommendation. A contentious issue, especially when councillors can override planning authorities for political reasons totally unrelated to planning.

Section 106 (ensures developers contribute to the community to compensate for the impact on new arrivals) is often used by councillors to block developments. They should be worked out mathematically, like the 0.04 swimming pools example above, but in practice if a councillor wanted to block a development they can make the Section 106 so onerous that no developer could meet the demands.

Last year Grant Shapps, then transport secretary, infamously vetoed council-approved plans to build four towers, including 132 affordable flats, in Enfield. Despite being adjacent to a tube station, Shapps blocked the development owing to a lack of car parking. (onlondon.co.uk)

Discretion in planning leaves developments in constant competition with the NIMBY instinct and erodes faith in the system when applications are declined on bizarre and illogical grounds. From our conversations with developers, we know that when there is a local or general election, many will delay submitting an application to the local planning department to reduce the chances of a politically motivated denial to their project.

Planning disproportionately affects SME developers

According to the Federation of Master Builders, in 1988 SME house builders in England built 40% of all new homes. Nowadays, it’s around 10%.

Every planning application, whether for 2 or 200 houses, is subject to the same technical assessments – ground conditions report, ecological survey, tree protection etc. Whilst an SME housebuilder may take 20 sites to deliver 200 homes, a larger builder often delivers that on just one site. For the SME builder, that’s 20 planning applications and 20 sets of reports.

As well as disproportionate upfront costs, SME builders are subjected to 20x more discretionary decisions. One respondent to The Homebuilders Federation 2023 survey stated ‘100% of my refusals in the last three years have been approved on appeal,’ creating unnecessary delays and costs.

Also, larger sites already earmarked for development, will experience a smoother run through the planning process. Not just because the principle of housing has already been established, but because when extensive consultation on a strategic site has taken place already, there tends to be less local opposition and less political lobbying. (p4planning.co.uk)

Planning reforms are key: replacing the discretionary planning system with a rules-based, tick-box system would motivate developers and provide project certainty. Using tech to automate the planning process will reduce pressure on planning officers - software platforms like Nimbus Maps and Searchland are progressing this.

The picture down the line

Currently, we're building around 200k houses per year so the gap between homes needed and homes delivered is getting bigger.

If planning applications and permissions keep dropping, and subsequently new house builds start dropping, then we'll have a big problem a couple of years from now.

Interest rates will inevitably come down at some point over the next 24 months, and wages will have gone up, meaning mortgage rates will be lower and relative buying power increased. Logically, demand will far outstrip supply, likely causing a spike in prices by 2024-2025.

Delivering to market for 2024/2025

If there is a price spike on the horizon, now is the time to be developing. We’ve already said in earlier Industry Insights that the volatile market of 2023 is a great time to be acquiring better-priced sites and getting into the cyclical development process at exactly the right time.

Now is when developers need to push through the planning process and aim to deliver to what will likely be a prime market by late 2024 into 2025.

What needs to be built

It’s worth caveating some of the data around planning figures though. For example, during the 1970’s home building rates were significantly higher than today – but demolition rates also were, meaning the net increase in dwellings in 2020/2021 was in fact higher than the 1970’s. (economicshelp.org)

The recent England-wide figures clearly demonstrate how beleaguered the house-building industry has become, and without question to the detriment of the UK economy, growth and of course home buyers. The lack of central government policy and housing targets is causing problems, but the deterrence to develop due to a taxing planning process does not affect the whole of England to the same degree and consideration needs to be given to where the shortage is felt most acutely.

Naturally, larger cities are far more affected with rented accommodation, affordable homes and social housing being in the shortest supply.

According to Shelter, there are 1 million households in England waiting for social housing. This is pushing demand into the private rental sector, where supply has been slow to keep up, and is now set to shrink even further after recent rental reforms and increased mortgage costs have led to profit squeezes on landlords.

More council and social housing is a key part of the solution, but considering the scale of the backlog, increasing the amount of private house building will be crucial. The UK’s ageing population also needs to be taken into account - building housing based on the needs of the elderly will free up homes for bigger, younger families.

Another issue is the 640,000 empty homes across England, with London being the worst affected due to investors speculating on rising prices. Nearly 1 in 3 homes in the City of London were classified as empty.  Tourist areas are also facing an ever-increasing rise of holiday-lets, Airbnb’s and second homes. For example, in Cornwall, 16,000 people are on the list for council homes, whilst 18,000 homes are reported as empty and 10,000 homes are registered for Airbnb. (Open Democracy/economicshelp.org)

Tourist areas are also facing an ever-increasing rise of holiday-lets, Airbnb’s and second homes. For example, in Cornwall, 16,000 people are on the list for council homes, whilst 18,000 homes are reported as empty and 10,000 homes are registered for Airbnb. (Open Democracy/economicshelp.org)

Gove's reforms

In his speech on the 24th July 2023, Michael Gove said the government would ‘concentrate our biggest efforts in the hearts of our cities’ and would be ‘using all the levers that we have to promote urban regeneration rather than swallowing up virgin land.’ (bbc.co.uk)

Gove wants to make it easier to convert disused retail units, and units such as takeaways and betting shops into housing and wants to ease rules on building extensions to commercial buildings and repurposing agricultural buildings.

To help speed up big developments, the government will invest £24m to train up planning authorities and £13.5m for what it calls a ‘super squad’ of planners to unblock certain projects - a development in Cambridge will be the team's first task.

Developers will be asked to pay higher fees to fund improvements to the planning system (again, disproportionately affecting SMEs).

Whilst the changes are a positive start, The National Housing Federation claims they are nowhere near the scale that’s needed and fail to directly address the housing that is in most short supply - social housing, affordable homes and rental availability. The head of housing charity Shelter praised Mr Gove for being a minister who is ‘not afraid to build’ but warned that plans to convert takeaways into homes risked creating ‘poor quality, unsafe homes’. (bbc.co.uk)

With the government anticipating a Spring election in 2024, it’s no surprise that they have announced measures to address the housing crisis. Nonetheless, Rishi Sunak is hampered by his own backbenchers where new housing developments have proved unpopular amongst Tory voters (and their MPs) in their leafy heartlands. This makes for a tricky position when demand for housing amongst younger voters struggling to get on the housing ladder is huge.

Also, critics are questioning whether developing brownfield sites can actually deliver the volume that’s needed, especially when house building in the UK is set to be at its lowest rate since WW2.

But as mentioned, regeneration in cities directly targets where the shortages are most acutely felt. By the time the election comes around, inflation should have normalised and interest rates could be lower, meaning the government might just have enough leverage for a ‘stick with us for housing and green space’ narrative.

A boost for SME developers

The good news for SMEs is that most brownfield sites are too small to be viable for larger-scale property developers, leaving the road clear for their smaller, more nimble counterparts. Potential sites will be made available for development by local authorities, meaning the planning application process should be significantly easier to navigate.

Based on the data for Q1 2023, the number of units that will have already begun, or are about to begin this year, are at eye-wateringly low levels. When supply couldn’t meet demand during the buying frenzy throughout 2020-2022, house prices rose by around 26% for detached properties and 13.4% for flats (Nationwide HPI). Figures around planning applications and stats point towards housing supply becoming even further reduced, meaning prices are likely to spike beyond those fast-paced increases we already experienced. Meanwhile, buyers who have been biding their time for two years or more, waiting for lowering interest rates, will be desperate to return to the market.

Again, with possible opportunities arising from new government policy, now is the time to be searching for sites and preparing to deliver to what will be a hugely under-stocked, over-subscribed market by 2025.

At Brickflow, we’ve been digging deep into the housing crisis across England and the UK and are currently working on a White Paper that analyses all aspects of the problems facing our housing market. We’ll be publishing soon, so keep an eye out on Brickflow.com.

Brickflow is a software company only. Our product is designed to be used by experienced property finance professionals to source and apply for development finance loans.

Property investors can search the finance market by using our software to model and analyse their deals, but they cannot apply for finance through Brickflow without a Broker. Speak to your Broker about Brickflow or ask us to connect you with a Broker.

Property development carries risk, including variables beyond the developer’s control. A property development loan is debt and should be procured with caution.

Brickflow does not provide information on personal mortgages, but your home and other assets are at risk if you provide a personal guarantee for a corporate loan.

Brickflow is a digital marketplace for commercial property finance. We connect brokers with lenders to source the best value loans, quickly and easily.

The inside track on property development in March 2023.

The inside track on property development in August 2023.

The inside track on property development in June 2024: Are Extended Property Transaction Cycles Here to Stay?